I’ve had an email from a high school student who’s writing an English assignment on careers he would like to follow. He said:

Would you answer a few questions about your job journey? I’m very interested in what you do.

His questions were fairly standard, and they made me realise how most creative careers are anything but. They’re unpredictable and weird. Here are my answers, and I’m really curious to see what other writers would say. If you’re game, do have a go in the comments.

What is your exact job title?

Author of fiction, creative non-fiction and writing craft books.

Though actually, I have several jobs.

I’m also an editor, producing books for publishers and individual authors, and magazines as well.

I’m a writing coach, teaching individual authors and also masterclasses.

I’m a ghostwriter, writing books for others.

And I’m a story consultant, working on computer games and indie movies.

You were probably expecting just one title and I’ve given you five.

Multiple jobs are the norm.

Many authors also teach, edit, run publishing imprints, contribute to the wider literary ecosystem. So do other people in the creative arts. I know actors who coach executives to be influential in meetings and interviews, and teach doctors how to give bad news to cancer patients.

Or they might have other jobs that are entirely unconnected with writing. Again, that’s quite usual. Recently I’ve interviewed an author who is also a rocket scientist and another who is a sheep farmer.

Why is this necessary? Primarily for financial survival – for most of us, writing books is not enough to make a living.

Also, this other work keeps you grounded. If you spend a lot of time in make-believe, you can lose touch with reality.

So if you’re considering this line of work, find a day job that will work while you inch towards your dream, or might help you get there. Look out for side hustles.

So here’s the first takeaway

Embrace diversification. It make your core art possible.

It will also make you a deeper human, more in touch with the world your readers live in.

What types of work do you do on a daily basis?

It varies. Not all of it is writing, by any means.

Most books are a cycle – research and planning (not much writing), writing and editing (lots of writing), publishing (not much writing).

If I’m researching, I might lounge on a sofa reading and taking notes, which will look very leisurely, but is essential to create a credible book. If I’m planning, I’ll sit at a table with index cards, which will look like a children’s game, but it helps me find the best way to use story elements and information. Then the writing and editing are a lot of time at the computer, creating the text, checking things. Here’s my writing process in pictures and here’s Nail Your Novel, which will guide you through the lounging, gaming and other stuff.

You have to love checking. There is more checking than you would believe. A wrong fact, an inconsistent description, a paragraph accidentally repeated can kick the reader out of the story. Other editors will usually be involved in this process, but it still creates a lot of work for you. After the book’s been checked to smithereens, there are other publishing tasks – formatting, writing copy for the back cover, proofing.

If I have a commission for another author or a publishing house, their deadlines take priority. Sometimes that’s a desperate rush – just before Christmas a publisher needed three books edited before the holidays. I shelved my plans and burned the midnight oil, but we all got everything done and were proud of the result.

Second takeaway

Although the main job description is writing, a lot of the work is not writing.

There’s another essential task that writers will do – networking. We’re constantly looking for ways to attract new readers to our books, so I write a blog and a newsletter. Writers network among each other too, to share opportunities and wisdom.

If a book is close to publication I do another kind of work – contacting reviewers, blogs, podcasts and radio shows that might be interested in featuring it. That’s time consuming and there’s a lot of silence – often you never get a reply, but you keep going. If a tree falls over in a wood and no one hears or sees it, it just lies there. You don’t want your book to be that tree. You keep going.

Third takeaway

You can’t survive if you don’t network.

What requirements/previous experience are necessary for a job like yours?

Boundless reserves of self-motivation and discipline.

You’re not in an office, surrounded by people who are also hard at work, or waiting for you to finish something they need. You could decide, if a book is proving difficult, to give up.

Online forums can provide supportive company, like an office, but choose them carefully. There are loads of ways to drag yourself further into a funk if you dwell too much on the frustrations. And online, distractions are just a click away.

So your writing and your books have to be a contract with yourself, a personal mission.

You might wonder about training. There are courses and qualifications, but not everybody does them. They make little difference to whether you get a book deal, though they might get you contacts. In that respect, doing a course is another form of networking.

And long before you ever think about taking a course, you’ll already be a writer.

You just find yourself writing, full stop. You also find yourself reading in a strangely alert way, dwelling on a sentence or a story twist, wondering why it electrifies your hairs, and the next time you write you will play with the words and place them more deliberately. Before you know it, words and stories are an instrument you are trying to master.

You might read craft books, go to classes, take a qualification, get feedback from a professional editor, and those are good because we all need to learn from other people. And there are definitely skills to learn. But most of the work is done by you, developing your awareness, practising on your own.

So here’s the fourth takeaway.

Writing is a temperament, a wish, a tuning of the mind to love language, and the shapes of stories, and the way words can enspell a reader, no pun intended (okay, maybe a little one).

Is it difficult to get a job in this field?

Yes and no.

Yes, difficult, because there aren’t many jobs writing books, especially fiction and creative non-fiction. There might be commissions, but you have to be already established.

But mostly you hack your own path. You become an author by writing a book, and seeing if you can get it published. Whether it is or not, you then see where that takes you.

The first book you write may not be the first book you publish. As I said above, there’s a lot to master.

Also, we haven’t talked about the luck of getting published and the option of self-publishing. Some people are lucky with publishing offers. Their work is exactly what a publishing house is looking for. Some get a deal for a later book after writing several.

Some self-publish. For that there’s no barrier to entry. You don’t have to pass any selection process. You just do it.

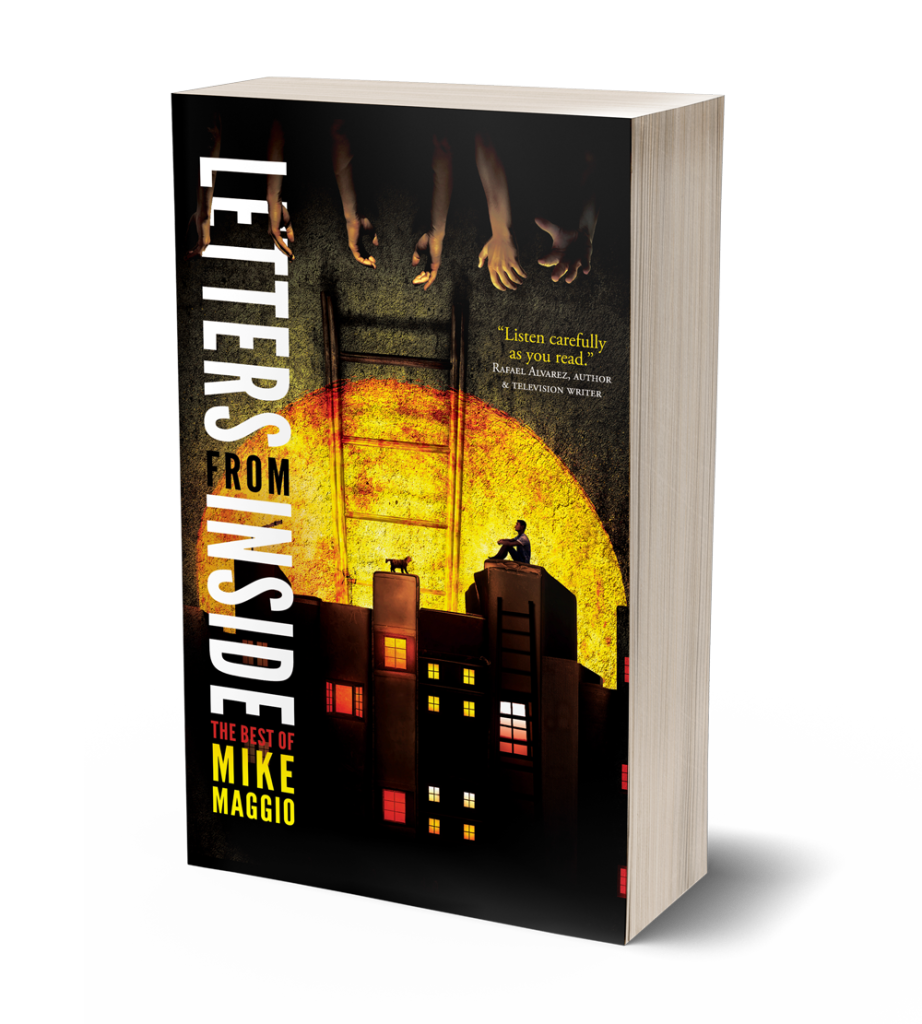

If that sounds easy-peasy, stop. Don’t ‘just do it’ unless you’ve had professional help. Remember I mentioned all the checking? Publishers, editors and experienced authors know what to check – and it’s stuff you never dreamed was important. You’ll also need help with the presentation – formatting, cover and sales blurbs – so that your book looks credible.

So although you can leapfrog the gatekeepers and start your author career completely on your own, don’t do it without help from experienced people.

Really important takeaway (number 5)

Take very good care of your reputation. Find out what the best people do and aim for that.

If getting into this field is difficult, how did you manage to land your position?

By trying the conventional routes, getting nowhere, and through that, finding the door.

I sent short stories to publishers and magazines, was told they were good but novels were more saleable. So I wrote a novel, and publishers and agents told me it was well written but too strange for the market. Meanwhile, I met various authors, all swimming in the same pool of luck/non-luck, married one of them (ultra-networking!), and got a chance at a ghostwriting job.

That was the door. A book came out, which I had made on my hard drive – my dream. More commissions came and I also discovered I was good at teaching other authors (another door). Then the self-publishing revolution took hold in the late 2000s and I was ready, with all the skills, to publish my own books and get good reviews for them.

Sixth takeaway

Expect a lot of false starts until something works, which will usually be unexpected.

Do you like/love the work you do?

Writing books is a vocation. A way you’re born and the way you grapple with the world. The page is my easy place, where I think and play.

An example. I had an idea about a man who fell into a glacier and was still there 20 years later, while his friends got older. It kept bothering me. It was saying something deep and sad about the human condition, about memory, about the great mystery of lost youth and the grand enigma of death. I made it into a novel, Ever Rest. It took a lot of work, but that work was also a personal crusade, to puzzle out why it was so powerful.

Seventh takeaway

I think this work is a personal mission, which is probably love.

Do you see yourself retiring from this job? Or is there another job you’d like to do next?

No.

Eighth takeaway

This is a way of life. I have to create. It’s how I fit into the universe.

Is there anything you wish someone had told you about this job before you decided to take it?

Not really. If they had, I wouldn’t have taken much notice. I was probably told all kinds of offputting things over the years, but I just kept going.

Keep going – that’s the ninth takeaway.

There’s a lot more about writing in my Nail Your Novel books – find them here. If you’re curious about my own work, find novels here and my travel memoir here. And if you’re curious about what’s going on at my own writing desk, here’s my latest newsletter. You can subscribe to future updates here.