What makes a poem a poem? How is it a different beast from richly written literary fiction? In prose, it seems, we can do most of what a poem can do, beyond just telling a story. Creative expression, profound thoughts, metaphors. We can even control how the text falls in the reader’s mind through our use of cadence and line breaks. What’s the distinguishing difference with a poem?

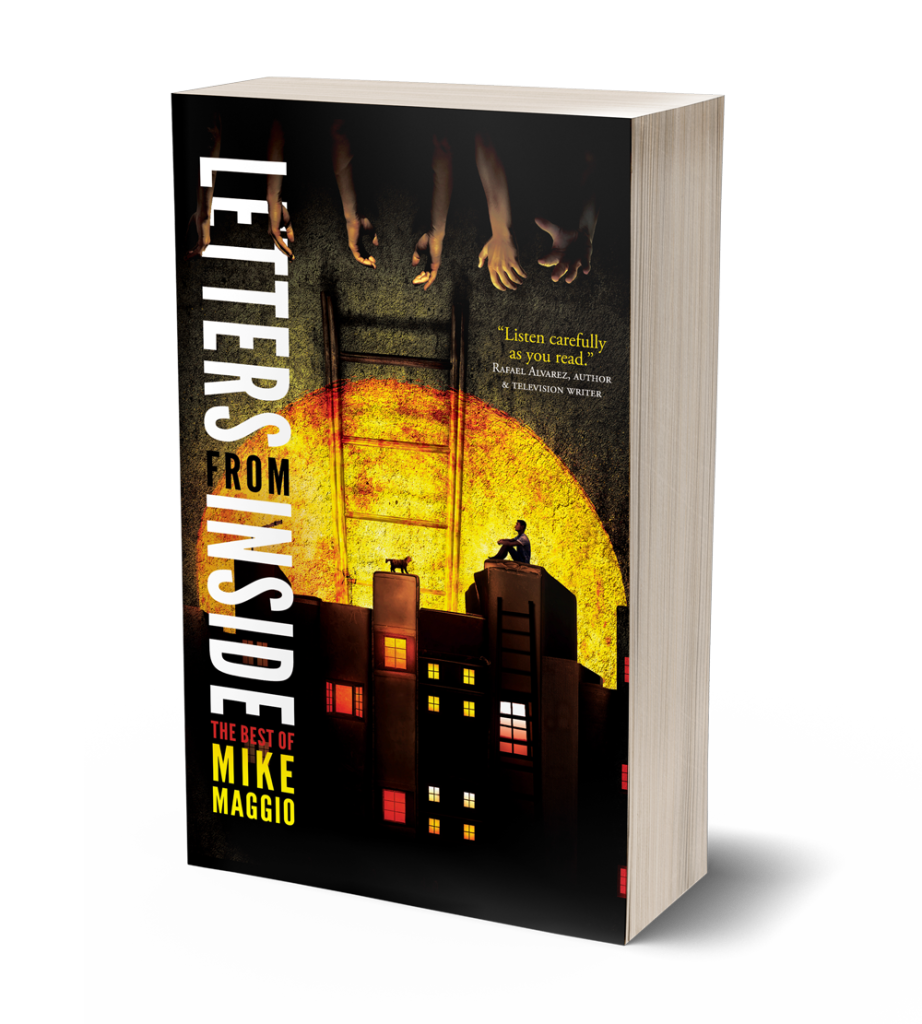

Mike Maggio is amply qualified to talk about this. He has several poetry collections (DeMOCKracy, Garden of Rain, Your Secret Is Safe With Me, Oranges From Palestine, and Let’s Call It Paradise, which won the Intranational Book Award for contemporary poetry). He was nominated as the 2020 Virginia Poet Laureate and he’s a judge in the Oregon Poetry Association’s annual contest. He also has three volumes of short stories –The Keepers, Sifting Through The Madness, Letters From Inside (I love that title). And two novellas – The Wizard And The White House, and The Appointment.

So, Mike, the overlap between fiction and poetry – and the boundaries?

I guess I could write a book on this but what you say fiction does is not far off from poetry: creative expression, profound thoughts, metaphors and line breaks. But poetry is very different from fiction. Line breaks, for example, can have a huge impact on the meaning and movement in a poem.

I work in both forms and when I get an inspiration, I know immediately if it’s for a poem or a piece of fiction. Poetry tries to make the most use of language and, in a sense, a poet’s job is to renew the language: to use it in ways it’s never been used before.

Furthermore, fiction involves characters and plots. In poetry, there are no plots except in a narrative poem, but even then, the plot is not thoroughly developed.

Hmm. Character and plot are the novelist’s true environment, even though we might also use the devices of language. That could be the distinction.

I think we poets seek mood, but then that is true of fiction as well.

Perhaps the difference is how poets use language. Poetry relies on a sparsity of language and on, as a professor I had in college used to say, the use of language and metaphor that is richly ambiguous. It allows readers their own interpretations.

And novels are the opposite of sparse. A novel is vast; an ocean. A poem is a wineglass.

And, of course, poetry is meant to be read aloud: to be listened to. You can listen to a poem in a language that you do not understand and still enjoy the sounds and rhythms. You cannot say that of prose.

Is there a common thread in your work? What are your enduring themes and signatures?

I believe that throughout all of my work, there is one consistent voice. That voice is concerned with social and political justice. I have been a social activist all of my adult life, starting in my late teens with the ‘60s social revolution and the anti-war movement.

My novel The Wizard and the White House approaches these concerns through the use of satire. The Appointment and Letters from Inside are less satiric. The Appointment is more absurdist, in line with Kafka, one of my most important influences, along with Nikolai Gogol. The title story in Letters from Inside is more dystopian. And Let’s Call It Paradise examines American culture through the lens of consumerism and how that masks any concept of justice and equality.

There are many influences in my work but the main ones are Kafka and Gogol. The absurdist point of view is one that captivates me.

You have a novel, Woman In The Abbey, coming out from Vine Leaves Press next year. What’s the significance of the title?

One of my main literary interests is gothic literature: novels such as Melmoth the Wanderer, Dracula and The Master and Margarita. And so I set out, by chance really, to write one.

I was actually working on a different novel – one that deals with immigrants and acculturation, based on my own background as an Italian American – when I saw a clip on TV about a monastery which housed both nuns and priests in separate wings. In this most austere, reverent setting, all kinds of non-religious activities went on, and I was inspired to write Woman in the Abbey.

It’s a novel narrated by the devil and involves all kinds of evil. Like most gothic novels, there is a damsel in distress, but the purpose here is to expose the evil of violence against women. And in fact, there are two women in the abbey: the innocent damsel who gets lost in this haunted abbey and the evil nun who resides there. The title is meant to be ambiguous like Letters from Inside which can be interpreted in two ways (you’d have to read the story to understand). I will also say, as a side note, that, having gone to Catholic school, I believe I got out all my anger at the nuns in this book.

You collaborate with poets, novelists, musicians and artists. I wish I had time to ask you about all of these – but can you give me some highlights?

A while back, I became the Northern Region VP for the Poetry Society of Virginia. So I organised a collaboration called Springtime in Winter which involved poets, composers, artists and student musicians. We had two composers, a number of artists who I paired up with the poets and five high-school musicians who were conducted by the high-school music teacher and who got to play this original music which was later recorded and put on a CD. It was a wonderful mentoring experience.

Most recently, I travelled to Italy where I worked with four Neapolitans (a poet, a poet/actress, an actress/director and a cellist) for a bi-lingual production called La Guerra è Pace / La Guerra e Pace. We performed it live and filmed it with a cell phone. The piece can be viewed on my YouTube channel: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x8n3x-8-82c

Is/was anyone else in your family creative? How have you ended up on such a creative life path?

Neither of my parents finished high school. But they had faith in me to follow my path. My maternal grandfather, an Italian immigrant, had a music store in Brooklyn at one point. Why, I don’t know. Whether he played music, I don’t know. But there was a piano in their house when I was growing up which, I believe, inspired me later to study piano. I had an uncle, my aunt’s husband, also an immigrant, who would listen to operas on his phonograph every Saturday. He would sit there and cry because, as you know, operas are tragic. I had an aunt who was a poet and editor though I think this came after I started writing. I had another uncle who was a one-time musician. So I guess you could say creativity runs in the family. My brother became a church organist and my son now is a serious student of the cello at Cleveland Institute of Music.

But perhaps the most important influence were my Italian grandparents. I remember as a child sitting in a room with them and their friends and hearing nothing but Italian, which I did not understand. So what does a child do? He sits quietly and listens. And what does he hear? The music and contours of the language he does not understand since he cannot make out any literal sense.

I believe that that experience influenced me to become interested in language (I’ve studied French, Spanish and Arabic and am now studying Italian), linguistics (which I have a degree in) and ultimately poetry.

And now, here you are. A charming origin story. Thank you.

Find Mike on his website www.mikemaggio.net and Facebook.

There’s a lot more about writing in my Nail Your Novel books – find them here. If you’re curious about my own work, find novels here and my travel memoir here. And if you’re curious about what’s going on at my own writing desk, here’s my latest newsletter. You can subscribe to future updates here.

Agree, mostly, and disagree some–different for everyone. Good post.

We all have our own ways, which is how it should be. Delighted to have you reading. And commenting.

Always great subject matter here. Am reminded of what Wayne Dyer once said; “There’s that guy’s way, there’s my way, there’s your way–there is no THE way.” And that’s the point of the Roz-posts–take what you need from a pretty good source here. Thanks R and Mr. Maggio.

‘Poetry tries to make the most use of language and, in a sense, a poet’s job is to renew the language: to use it in ways it’s never been used before.’

I loved that thought of Mike’s. I tell my creative writing students that poetry is THE most creative form of creative writing. There are no rules, unless you choose to follow them (and then you need to do it properly).

Thanks for the interview and thanks for the write-up.

Thanks, David! I also love the idea of renewing the language. That’s a poet’s description.