What makes a story science fiction? Is it an otherworldly location, the science, the time in which it is set?

What makes a story science fiction? Is it an otherworldly location, the science, the time in which it is set?

I’m thinking about this because of a review I saw this week of a novel billed in The Times as science fiction, which sounded rather disappointing – and it’s put me on a bit of a mission.

I haven’t read the book so it would be wrong of me to name it, but it concerned a new planet populated by humanlike aliens. The main threads are the bringing of God to the indigenous people, and the exploitation of its resources by mining companies.

It seemed this story could have been set anywhere. The human challenges were no different from those in a historical novel. The other-world setting didn’t add anything fresh, except maybe to save the writer some research. (I see a lot of science fiction – and fantasy – novels that are written for this reason. If you invent the world, you can’t be accused of getting it wrong.)

But shouldn’t we be doing something better with science fiction (and fantasy)?

Bob Shaw says, in How To Write Science Fiction, that science fiction’s defining quality is that it deals with ‘otherness’. Whether it’s in the future, the present or the past, it’s about realities we don’t have at the moment.

He also says that the central idea in a science-fiction story is so important it should have the status of a major character. It needs to be developed and explored. It changes what people can do, creates new situations that illuminate the human condition. It adds a new quality of strangeness. And Shaw also says if that concept is taken away, the story should fall apart.

One of Shaw’s own short stories illustrates this. Light of Other Days sprang from an idea about an invention called ‘slow glass’, which allows you to see an event or a setting that happened years earlier. And so a man whose wife and child died in an accident can still see them, every day, in the windows of his house.

Take, by contrast, Andy Weir’s The Martian. An astronaut is trapped on Mars and has to make enough air, food and water to survive. It’s genuinely an addictive read and I loved it, but it could just as easily be happening in Antarctica or on a deserted island. The science provides the particular challenges and the possibilities, but it does not change the human essence of the story.

Take, by contrast, Andy Weir’s The Martian. An astronaut is trapped on Mars and has to make enough air, food and water to survive. It’s genuinely an addictive read and I loved it, but it could just as easily be happening in Antarctica or on a deserted island. The science provides the particular challenges and the possibilities, but it does not change the human essence of the story.

We’re used to thinking that any story outside the Earth’s atmosphere is science fiction, but they’re not. They’re survival stories. But take the slow glass out of Light of Other Days and you’d have no story at all. That’s science fiction.

The Martian is a great read. The other novel may be too. But it’s a pity if the critical press and the literary community are presenting them as examples of good science fiction.

Science fiction should be a literature of the imagination. I think it’s a shame if we forget this. The same goes for fantasy – Neil Gaiman’s Graveyard Book is a deeply invented world, and very different from The Jungle Book, which inspired it.

Science fiction should be a literature of the imagination. I think it’s a shame if we forget this. The same goes for fantasy – Neil Gaiman’s Graveyard Book is a deeply invented world, and very different from The Jungle Book, which inspired it.

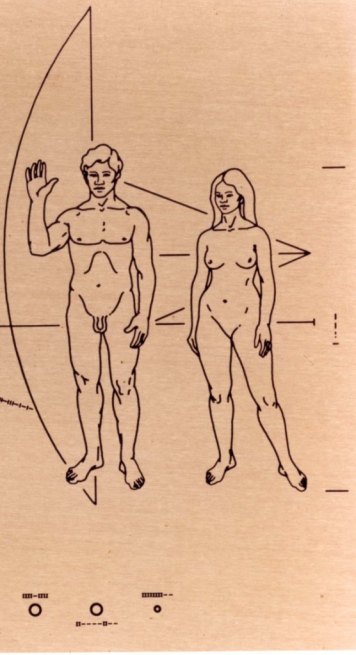

We only have to look at our own, real past to see how science fiction and fantasy should grapple with the idea of transformation. Every invention in the history of humanity shows us this. Think of electric light – we can change society and the very fabric of life with an idea like that. With phones – and particularly mobiles – we are reinventing the way society works, saving lives and creating new types of crime. With scientific narrative non-fiction like Rebecca Skloot’s The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks we also have a model for writing great science fiction. We can examine the impact of a scientific discovery and the quantum changes it brought, in individual lives and for global corporations.

Science fiction works on this same continuum, the scale of human change. A great science fiction idea should allow us to send humanity to startling new places with new advantages, cruelties and injustices. And those are places in our souls, not just other planets.

Science fiction works on this same continuum, the scale of human change. A great science fiction idea should allow us to send humanity to startling new places with new advantages, cruelties and injustices. And those are places in our souls, not just other planets.

So – rant over. I’m hoping this isn’t too abstruse or marginalising for some of the regulars here, but you do know how I love the strange … Do you write science fiction or fantasy? What are the ideas you’re grappling with? How do you refine them or test if they will be bold enough? Would they pass the Bob Shaw test?

POSTSCRIPT How could I have forgotten one of my favourite things about science fiction? It took Dan Holloway to remind me of it in a comment – the reason these ideas prove so beguiling is that they are metaphorically resonant. They enable us to see aspects of humanity that aren’t yet visible. Do read Dan’s full comment below.