I’ve had this question from Elizabeth Lord: I have just finished your book Nail Your Novel and found it extremely helpful for the rewrite phase of my novel. You mention graphs as a way to see where plots are plodding and character arcs intertwine – do you have any examples?

I’ve had this question from Elizabeth Lord: I have just finished your book Nail Your Novel and found it extremely helpful for the rewrite phase of my novel. You mention graphs as a way to see where plots are plodding and character arcs intertwine – do you have any examples?

What a good question! Diagrams coming up.

First, though, a bit of explanation. Readers get bored if the plot appears to be predictable – ie the characters start with a goal and proceed doggedly towards it, step by step by step. This is a linear plot and it looks dead dull, like reading the syllabus for an education course, not a story. So when the characters have a clear goal at the start, we try to introduce developments that upset expectations. They’re going on the Orient Express? Great. Make one of them miss the train. Now everyone has a new problem that matters far more.

The major changes diagram

So your first drawing exercise is to go through the plot looking for points where you throw in a development that changes the characters’ priorities in a significant way. Make a ‘didn’t expect that’ diagram.

You want several of these developments, BTW, and they’ll probably be the main turning points in the story. Note also that they’re emotional. They’re about changing the characters’ goals – the things they want, the things that matter to them. So early in the story, they’re trying to catch a murderer. By the end of the story, they’re trying to stop the murderer killing their wife. Or murderer and detective are embroiled in a towering love affair.

The highs and lows diagram

Another helpful diagram might look at the main characters’ emotional state throughout the book. You want them to feel increasingly pressured and troubled, and you want their worst moment to be the climax of the book. So try a diagram where you look at their levels of joy and achievement versus despair. The joy part isn’t so important, although you want to give your characters a few breaks so that the disasters are more agonising – and also to show what matters to them. Make sure the despair increases in magnitude as the story proceeds.

The un-convenience diagram

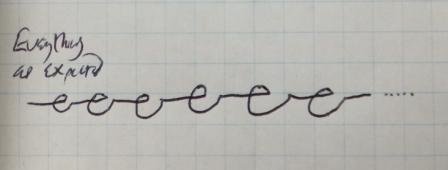

You can look for smaller reversals too. You might not realise you’ve made everything too easy for your characters. Every time they need to accomplish something, make it harder than they expect. Or make it backfire. You can check on this by going through your manuscript and drawing a little circle whenever you’ve thwarted your characters.

If you have a lot of little circles, you’ll probably keep your reader gripped. If you haven’t, you know to throw some spanners into their spokes.

Compare your plot strands at a glance

If you have several plot strands or main characters, you could combine them on one diagram and use different colours. Thus you will see, at a glance, how your character arcs intertwine and if you like the harmony of their highs and lows. Or you might spot a general lull where several characters seem to be having a successful run – in that case, it might be good to rework the story and introduce a setback or twist. If you’re the kind of person who has music manuscript paper lying around (how stylish of you), you could draw your diagrams on the staves, like lines for different instruments.

X-ray your plot

The serious point is this: these exercises are ways to extract and visualise important plot mechanisms that might otherwise be invisible to you, and help you fix problems with the structure and pacing. Have fun!

Elizabeth’s question was inspired by a section in Nail Your Novel: Why Writers Abandon Books and How You Can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence. There’s also a lot more about plot and structure in Writing Plots With Drama, Depth and Heart: Nail Your Novel 3.

Do you draw diagrams to assess your plot – or any other aspect of your book? Share them here!

I use diagrams frequently. I usually use a white board for bubble diagrams and time line grids, taking photos of the results so I can preserve them and store them with the rest of my project files in Scrivener. I sometimes use a program called Scapple (also from Literature & Latte) to create diagrams, but there’s something about stepping away from my computer and drawing with colored pens that helps my ideas flow better.

I usually start with a basic framework diagram that divides the story time line into four parts. It’s essentially the three-act structure with Act 2 split at the middle. (My story structure is based on a merging of theories from the works of Ingermanson, Brooks, and Bell.) I overlay a “factions” grid on top of the time line so I can keep track of who does what when. For example, if you envision the X axis as the structure time line, the Y axis represents the different factions. I note significant events within the resulting grid cells.

Although I definitely consider myself a planner, I don’t plan down to the scene level. I start with a basic idea of where the story needs to go, but I don’t know exactly how I’ll get there until I start writing scenes. (Bell calls this “the headlights method.”) The further I get into the story, the clearer the rest of it becomes. After five novels, I find that I do best if I finish Part 1 before attempting to plan Part 2 in detail, and so on through the first draft.

I thought you’d be one of the commenters, Daniel! I figured, if anyone does diagrams it’ll be my fellow system-guy Marvello. Thanks for sharing your grids and charts.

Interesting idea. Have never come across this or thought of it myself. Will have to consider it for my next book.

Have fun with it, Tanya. I love anything that looks vaguely like playing. Highlighter pens, diagrams, summaries in tiny writing…

Reblogged this on Notes from An Alien and commented:

Today’s re-blog, from Roz Morris, will zap stalled plot-intentions 🙂

Reblogged this on s a gibson.

I’ve never used diagrams before, but my latest WIP has become so complicated I may just have to start mapping the plot out to make sure I don’t leave any glaring holes, amongst other things.

Enjoy the new feeling of supremacy and control, Andrea!

lmao! I’m still at the head scratching stage. D:

Reblogged this on Don Massenzio's Blog and commented:

Here are some great plotting tips. Please enjoy this post.

Another trick to get those reader-addicting dips and rises is to pretend that you’re a Charles Dickens or one of his colleagues writing a serialized novel for a popular nineteenth century magazine. Each issue has to both satisfy readers and make them eagerly await the next.

A practical application of that would be to consciously write each several-thousand-word chapter as if that were all your readers were allowed to read that week. In that one chapter, you strive to reconcile some former problem for your characters while introducing a new twist. Keep each individual chapter from being boring and predictable, and your entire book becomes a page-turner.

This has an added advantage of also working for those of us who aren’t that into outlines, charts and graphs. Doing a chapter without exhaustive planning is easier than doing a book that way. You may even find the plot taking a different path from that you’d planned. Tolkien had that happen several times while he was writing The Lord of the Rings.

Having friends review what you’ve written chapter by chapter as it progresses is a way to get the same effect. That is important because, sadly, today only a few magazines serialize fiction. We need a substitute.

For Tolkien, that serializing for friends took place at the Inklings meeting in a restaurant in the thirties and by sending copies of his latest to his son Christopher, stationed in South Africa during WWII.

–Michael W. Perry, co-author of Lily’s Ride and of Untangling Tolkien

Hi Michael! I like the idea of writing each chapter as though you’re afraid the reader might put it down! Thanks for these lovely examples.

Reblogged this on My Writing Blog and commented:

Brilliant idea!

Reblogged this on O2b heavenly minded and commented:

Here’s an interesting post on how to visualize each character’s path in your novel. Enjoy!

Great suggestion, Roz. I found myself wondering what the x-axis is. It surely has to be finer grained than Act I, II, III. Chapters? Scenes? Significant incidents? Page number? I’d opt for chapters, so that I can see the whole novel at a glance. I’m sure mine would reveal several long flatliner phases.

BTW: Why don’t such fantastic helps as #Scrivener include graphic tools for visualising one’s WIP?

Victor – great to see you here! You’ve raised a good question. You could make an x-axis out of all sorts of things. I’d go for scenes rather than chapters because they’re the smallest measurable unit in which you want a change. I don’t know that it would be as much help to measure the book by chapters as the breaks are more arbitrary and you might have them for many reasons – a switch to a different area of the story, a moment of emphasis, a break in the timeline. But get the scenes right and book will hum along.