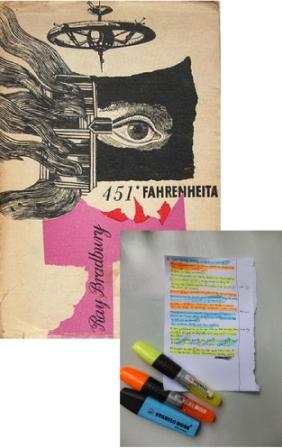

I get a lot of emails about the beat sheet revision exercise I describe in Nail Your Novel. I’ve just prepared an example for my Guardian masterclass using the opening of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 so I thought you guys might find it helpful.

I get a lot of emails about the beat sheet revision exercise I describe in Nail Your Novel. I’ve just prepared an example for my Guardian masterclass using the opening of Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 so I thought you guys might find it helpful.

Bradbury is one of my heroes for the way he explored science fiction ideas in a lyrical style – and indeed he described himself as a writer of fables rather than SF. Strong influence there for my own Lifeform Three, in case you were wondering. Anyway, creating the beat sheet made me admire Fahrenheit even more so I thought it would be fun to share my discoveries here. (Discreet cough: spoiler alert…)

First of all, what’s a beat sheet?

It’s my absolute rescue exercise for revision. Think of it as an x-ray of your draft. It lets you check the structure, pacing, mood of scenes, character arcs, keep control of plots and subplots, wrangle your timeline – all the problems you can’t see when you’re lost in a sea of words. And you can learn a lot if you make a beat sheet of a book you admire.

Here’s how it’s done. You summarise the book, writing the scene’s purpose and add its mood in emoticons. Either use an A4 sheet and write small, or a spreadsheet. Be brief as you need to make this an at-a-glance document. Use colours for different plotlines or characters. Later you can draw all over it as you decide what to change. This is the first third of Fahrenheit 451.

- Intro Montag, startling wrongness, brutality of burning scene :0

- Meets C, explanation of fireman job + role. Establishes M’s alienation from

natural world & how people are isolated - M ” home. Wife overdosed :0 !

- Horror/desperation of rescue, texture of deeper sadness :0, concealment of

true feelings, everyone’s doing this - Morning. Wife doesn’t remember. M isolated with the horror. TV gives people substitute for company

- M meets C again, disturbed by her, fascinated by her curiosity & joy

- Intro to mechanical hound. Brutal games other firemen play. M hated it & feels threatened by hound. Guilty secret :0

- Friendship with C deepens. She’s misfit. Explanation of how kids are

- taught in school. Other kids as brutal as firemen. M increasingly drawn to her outlook

- M progressively more alienated & uncomfortable :0 Goes with firemen to house. Steals book ! Woman defends her books & sets fire to herself !!

- Men shaken. Captain B pulls them together

- M too upset/afraid to go to work. Tries to talk to wife. Wife’s priority is for him to keep his job & buy gadgets. Can’t comprehend or notice M’s distress :0

- B visits – pep-talk, history lesson. Wife finds concealed book ! Does B know?

- M confesses :0 ! Is B friend or foe? ? !

- M confesses to wife ! He has 20 books !! Now she could be in trouble too. Furious. Persuades her to start reading !!!…

So that’s how it’s done.

Now, even more delicious, what can we learn from Mr Bradbury?

Introduce the world and keep the pace moving – variety and contrast

Introduce the world and keep the pace moving – variety and contrast

Beginnings are tricky – what information do you show? Bradbury gives us a lot, but makes it memorable and entertaining with his use of contrast.

First is the startling close-up of the books being burned and the brutal relish in his description. Next is the conversation with Clarice McLellan, the kooky neighbour who seems to come from a completely different, gentler world. Third scene is Montag’s home life. (We can see this from the colours – blue for work, orange for the conversations with the intriguing girl, yellow for home.)

We’re probably expecting the home scene, so Bradbury keeps us on our toes and breaks the pattern. It’s no regular scene of domesticity. It’s Mildred Montag’s suicide bid. There follows a horrifying scene where technicians pump her out, routine as an oil change. It builds on those two emotions we’ve seen in the earlier scenes – the brutality from scene one (brought by the technicians), and the sensitivity from scene two (Montag’s reaction). In just three scenes, the world is established – and so is the book’s emotional landscape. A brutal, despairing world and a sensitive man.

Connecting us with the character

In the next scene, Mildred is awake, chipper, and has no memory of the previous night. Only Montag knows how dreadful it was and he can’t make her believe it. She is only interested in talking about the new expensive TV gadget she wants. This confirms Montag’s isolation and disquiet. And ours. We are his only confidante. We’re in this with him.

Change

In each of those scenes, something is changing – Montag is being surprised or upset (or both). Although Bradbury is acquainting us with the world and the characters, he is also increasing Montag’s sense of instability. As you’ll see from the beat sheet, the later scenes continue that pattern.

Pressure and relief: reflects the character’s inner life

Look at the emoticons. They show us the mood of each scene and, cumulatively, of the book. But successive scenes of pressure (action, perhaps, or upsetting events) can wear the reader down. That’s one of the reasons why we might have a moment of relief – downtime around the campfire, or a brief flash of humour. These relief scenes often carry enormous impact because of the contrast.

Fahrenheit 451 builds this atmosphere of a brutal world, and we notice it quickly. The only relief is in the conversations with Clarice – so the reader’s need for relief mirrors Montag’s internal state. Reader bonded to the main character by the author’s handling of mood. What perfect, controlled storytelling.

I could go on, but this post is long enough already. And we need time to discuss!

The beat sheet is one of the tools in Nail Your Novel: Why Writers Abandon Books and how you can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence. More here

The beat sheet is one of the tools in Nail Your Novel: Why Writers Abandon Books and how you can Draft, Fix and Finish With Confidence. More here

And more about Lifeform Three here

Have you made beat sheets of your own novels, or novels you admire? Are there any questions you want to ask about beat sheets? Or let’s carry on the discussion about Fahrenheit 451. Ready, aim, fire

Ray Bradbury may have referred to himself as a writer of fables, but parables might be a more apt term. Fables generally use animals to teach a moral lesson. Parables typically use people to teach their lessons and, more important, shouldn’t be pushed too far. Everything that happens in a parable isn’t a lesson.

The parable about the prodigal son gets pushed to far when people try to find moral significance in the other brother’s behavior. He’s just there to point out that the returning son doesn’t deserve the welcome he’s getting, and thus to offer the father a chance to explain that welcome. Attempting to make him “jealous and that’s bad” exceed the intended limits of the parable. His motives are never given, much less treated as bad.

In the same fashion Fahrenheit 451 falls apart if you push it too far, specifically the sheer idiocy of having people attempt to memorize entire books to preserve them. Even if all printing is restricted, you can write out multiple copies of a book by hand far faster than you can memorize it and with far greater accuracy. Ten copies well-hidden will preserve that book far better than a single memorizer who can be exposed and either jailed or killed. If there’s a meaning to that memorizing, it’s simply to stress how important it is to form groups to keep books alive.

Also, if I remember right, Bradbury wrote the book to condemn its replacement in many people’s lives by television. Most people in the tale don’t care that books are burned because all the entertainment and mood alternation that they think they need comes from television. You’ve described above how that’s not actually working in the wife’s life.

I tend to have the same attitude toward music. Many people today use music as a mood and mind altering drug. The songs they listen are a substitute for dealing in a more complex and direction fashion with their life ills. “I feel down, this song makes me feel better” often doesn’t deal with why they feel down. They need that music fix over and over again.

This Youtube video illustrates that: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ihGCj5mfCk8

The song is about having gotten over a breakup with a boy friend, claiming “I’m stronger without you.” It’s being extended to cover the different and more complex set of feeling that come with a diagnosis of leukemia. “I don’t need you ex” is being used to say “I don’t need you leukemia.” I know. I worked for sixteen months on the very Hem-Onc unit where that was filmed. I cared for patients just like them. I’ve even written a book on what it was like.

The problem is that most music (like television) lacks the greater complexity, range, and versatility of literature. Huge swaths of both (particularly music) devoted to the ups and downs of romantic love. Almost none deal with life’s other issues, particularly facing a potentially fatal illness such as leukemia.

When we try to make a “Stronger” about getting over a boy friend fit with facing a cancer, it’s doesn’t quite fit. It leaves a lot of loose ends. I don’t need you boyfriend doesn’t deal with all the medical and emotional support that children and teens battling cancer do need. They must have others. You see where the song misses in all the lyrics’s first-person pronouns and the fact that, to fit with the words, the lip-sync video has to show so many of those singing lying alone in bed.

The same is true of those in Bradbury’s F-451 world. Like the protagonist’s wife, their needs aren’t being met by television. They need the broader and more complex worlds of literature. Of course, stories and books aren’t a universal cure either. But they are, or at least can be, far better than a TV show or a song at helping us sort out our lives.

And yes, some books are trash too. They drug us into passivity rather than give us the understanding and resources to change.

Hello Michael! Such rich discussions here.

Your point about parables, fables and the literal raises questions about one of the fundamentals of story – persuading the reader to suspend disbelief. Quite often we’ll accept things while under the story’s spell. Later on we might think ‘hang on’.

Or we might write a synopsis and think the plot events sound very lame when stripped away from the atmosphere, the involvement with the characters. But on the page, those events work fine.

Or sometimes writers don’t get everything perfect! Although I didn’t mind the book people in F-451. Perhaps that was because it worked for me, or maybe it was because the emotional relief of Montag’s getaway was strong enough to override it. I also find a pleasing echo back to the way that storytelling originally worked – with voices around the campfire. But that’s a personal view. We have different levels of acceptance.

It’s funny you should mention the parable of the prodigal son. Actually, I always thought the prodigal son was a challenge. Its message, if any, seemed to be that some people will always be treated well, even if others seem to deserve more. It might also demonstrate that parables are sometimes not much different from nonsense. That was certainly my reaction when I was taught it at school and teachers were trying to extract a worthy message. To me it looked like a lesson in how life was unfair and operated on mysterious rules.

Your point about music… oh this is very interesting, and touches on something I’m exploring in my current novel. I wish I could discuss it with you more, but it’s too soon for me to have conversations about it without discharging the need to write it. Maybe another time. And I’m in awe of people who have tackled – and helped other people tackle – these unimaginable experiences.

I do think it’s strange how certain artforms have become this drench against complexity. And also how they have become background. Music, TV – even film – are often on as wallpaper. The funny thing about reading is it’s not like that. You can’t have a book ‘on’ as background. Books are not background. Reading is a sit-forward experience. I like that.

Suspending belief…. yes I do have a problem with that. I guess I can blame that on majoring in engineering. “Show me the science,” I think, “Describe the physics.”

Put a story in an obviously fictional or different worldly environment, and I’m fine with that. Call it magic and Bilbo’s invisibility ring is fine. Create an invisibility ring in 2015 Chicago with technology, and I say, “Whoa, give me some plausible explanation for how it could have been invented so quickly. Put it in 2115, and I become more accepting.

“To me it looked like a lesson in how life was unfair and operated on mysterious rules.”

Keep in mind a constant message from Jesus. He would point out to his listeners that their view of God was so low, even many humans were more forgiving (the prodigal son’s father) or giving (a neighbor and a judge who will help you if only to be left alone. The parables have a single message like that. Extend them far more broadly, for instance to the sorts of things Gandhi said about the Jews giving flowers to their Nazi executioners, and they become madness.

I’m not sure working with kids with leukemia is an “unimaginable experience.” I did my best in the book to make it seem within the abilities of almost anyone with the right medical training.

It is true that when I oriented on days and saw those children from perhaps twenty feet away, working with them was the very last thing I wanted to do. Then I came on night shift and discovered my position was caring for them. I flipped within hours to wanting to work there to the exclusion of all else. Viewed from a distance, those kids seem scary. Viewed up close, they became frightened children in need of love. I often use that to remind myself that a reality that is experienced up close and personal can be very different from how we imagine it or view it from a distance.

There are a number of books written by the parents of kids with leukemia and a few by teens who’ve had it. I wanted mine, My Nights with Leukemia, to describe what it was like to be a caregiver. As such, its primary audience was nursing students and nurses.

One goal was to challenge them to take on something emotionally challenging. I did that because nurses, of all people, who heard about that would say, “Oh, I could never work there.” “Yes, you could,” I say. I even draw a comparison to the Crimean war, where English nurses reared in affluence where they were expected to faint at the sight of a drop of blood took on the horrors of military hospitals and remained calm, caring and professional. Many of us can do far more than we think or imagine. Don’t sell yourself short.

Something similar could be done in a movie and could even be done well. But the hitch is that creating a movie is very expensive. It has to appeal to a large audience. In practice that means only a small number of popular plot paths. In all likelihood, a movie wouldn’t be about the reality of wartime nursing–the endless stream of badly damaged soldiers who die or get patched up and sent further from the front. To retain an audience, it’d need to create a romance with one such soldier and let the others fade away. What I did in the book, give story after story of the kids I cared for, works in a book, but it would be hard to pull off in a movie.

There are a few specific areas that a movie scene can accomplish what would be difficult in a book. There’s a scene in Predator that illustrates that. The well-armed special forces team has encountered a foe that may be more than they can handle. There’s a young woman they’ve taken as a captive and Arnold Schwarzenegger approaches her with a whopping big knife. Nothing is said, but a viewer will instantly think, “Is he going to kill her as useless baggage?” Instead, he cuts her free. The message is clear. What they’re facing is so terrifying, they are now allies not enemies. That message is best done visually and must move quickly, it’d be hard to put that into words on paper. Some things are best said without words.

But that said, a book can do much, much more and, because it doesn’t require huge production costs, it can target niche audiences.

Music can do more than it typically does. But the medium still limits severely what can be said. Most music plots, when they even have one, can be summarized in a short paragraph, And to make a living at it, most musicians feel they must stick to a few basic themes and deal with emotions rather than ideas. That’s as true of a typical rock song as of Beethoven’s Fifth.

For instance, the closest song I know to My Nights with Leukemia is a German one I heard in a music appreciation class. A father is traveling through a haunted forest at night with his son on the saddle in front of him. His son tells him of a creature he sees that the father recognizes as the death angel. In stanza after stanza, as the son describes the creature coming closer, the father drives the horse harder, as represented by the music becoming faster and louder. Finally, he breaks out of the forest and lets the horse come to a stop. He discovers that his son is dead.

That’s the same message as some of the stories in My Nights, but there’s no way all the full complexity of a even a chapter-long narrative can be introduced into a song. A parable, like a song, can have only one simple message. A book may have one overarching theme, but it can weave many complex stories together.

“You can’t have a book ‘on’ as background. Books are not background. Reading is a sit-forward experience. I like that.”

Exactly right. People often like to talk at movies and concerts. They’ll tell you to shut up if they’re reading. Reading forces the reader to imagine the scenes and the characters. You have to be involved.

That’s also why, before The Lord of the Rings movies came out, I did my best to get friends who’d never read the book before to read it. You’ll never get a chance to imagine the book for yourself once you’ve seen the movies, I told them. You’ll just see the movie characters.

–Mike

The book memorizing people of F-451 are puzzling and were pretty amazing to me the first time I read the novel. I guess they can tell a story to people who do not read or do not want to break the law by reading an actual book. Also, paper copies can be discovered and burned or decay and be lost forever. People memorizing stories and passing the stories down through the generations is the old way, the way things were before copying by hand (for the literate) and printing technology was improved for the masses. If you want to keep books but not technology, make the books be human. It’s man vs. machine that way.

Thank you for the sample of the beats!

Hi Tina! Those are good reasons to accept the book people. And who knows how much Bradbury thought about it consciously? He might have gone with an emotional decision, a hunch – ‘this is how storytelling always used to work, it feels right to me’. It has other resonance too – about books coming to life, and representing a fuller way to live.

Or am I just reading that into it because I didn’t find it unsatisfying? Indeed, I feel that most of the rest of the book was more satisfying. The end hardly seemed to matter because I’d already been on most of the true journey. That’s a risky claim. Should we ever say the ending didn’t matter? Are we finding here that, in spite of our analysis tools and our wish for guidance, that storytelling is an art as much as it is a science?

Or should we all be getting some sleep instead of talking ourselves round in circles? (Nearly midnight chez Morris LOL)

Keep in mind that oral traditions were typically poetry that followed some metrical standard that aided memorization and might include a host of cliches such as “wine red sea.” They were also memorable, in part, because what was passed along was easily remembered. Any out-of-synch phrasing was dropped or modified to something easier to recall.

Also, pre-literate societies have good oral memories. Having no books to consult, they have to remember spoken words. I believe I’ve read of studies that find that when a society become literate, oral memory declines. Perhaps the parts of our brain that’s used for the former become taken over by the latter.

It is a matter of wonder that our minds are able to learn to read relatively easily despite the complexity of the operation. Only a few centuries ago, literacy was rare, so it doesn’t seem to be something we’d be hardwired to do like we’re wired for speech. At 200 wpm and more, we have to decode shapes into letters, string the letters into words and attach meaning to those words in context, understand the whole, and perhaps even reflect on what we’re reading.

——-

And yes, maybe I’m being a bit picky jumping all over Bradbury about memorization. The key point is perhaps that in 1953 he realized that that ‘medium is the message,’ meaning that how ideas are conveyed shape what can be said and how it is understood. Reading he saw as healthy. Too much TV as unhealthy.

To give an illustration of perhaps how a medium starts to shape the message, about two years ago I watched several episodes of a 1950s TV drama show–I believe it was General Electric Theater. It was a bit like watching a play because early TV did model itself on plays. The screen was literally a stage.

I was surprised at the range and emotional depths they were attempting to convey. One was about a mediocre boxer who’d become so punch drunk that he was being banned from the sport. Unable to make a living he was condemned to hang around a cheap bar talking about his glory days with other abandoned boxers.

Quite frankly, I don’t watch television any more. But from what I recall a few years back when I did and what I hear about shows now, it’d be unimaginable for today’s television to cover anyone as ‘uncool’ and a derelict boxer, much less try to get us to sympathize with him. On today’s television, decadence and narcissism rule.

——–

That’s almost as depressing as an article I read by a college English literature teacher of many years. There was a time, she wrote, when students who’d not read “The Lottery,” were shocked by it. More recently, she found that, even if they’re not read it, they found the stoning at the end no big deal. They’d become jaded and unshockable. Something vital had been lost.

I believe that it’s good to be able to deal with anything that comes up, no matter how terrible or unexpected. But you can retain your ability to act without losing your ability to be shocked or outraged. In fact an inability to shocked often means that people who should act don’t. They remain passive observers. For them, life has become a movie or TV show.

It’s what C. S. Lewis was criticizing in The Abolition of Man. Imagine that our body organs represent three aspects of our personalities: the head is our reasoning skills and the bowels are our emotions, including our ability to be outraged. Uniting them together is our heart, the seat our courage. Remove the ability to be outraged, deprive people of courage, and we become minds that do little more than store facts. This is how Lewis put it:

“In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue and enterprise. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful.”

——-

–Mike

Why does Bradbury have people memorize the books? Because that expresses the theme of the novel – we *are* the books we read; they are part of us. Copying each book out ten times and hiding the manuscripts wouldn’t get across the sense of intimacy, devotion and identity.

It is important that in the days of the internet we don’t forget that literature is capable of being read this way. It’s not just a description of events, like “a movie shot in prose”. We will find the experience richer if we are able to see the novel as a work of authorial subtlety with layers of meaning. Moby Dick isn’t just a big white whale, you know 😉

Now, I don’t know how we got onto the prodigal son, but that one really is baffling. Only Jesus knows what he was trying to do there.

Book memorizing. Not so absurd. In fact it is tradition. My mother was an English teacher from the time period that this was written. It was most common to have assigned memorization. I can still recite large swaths of Keats, Chaucer, Shakespeare and the like from “spotting” her students over the years. In the American West, it was common to have someone in the community who could recite Shakespeare and the Bible. And very prized if someone could have been schooled with enough Latin or Greek to deliver some of the Classics via memory. Homer being especially popular. From my own very limited experience of my childhood memorizations, I can attest that you experience the books and plays much differently having memorized even small bits. Suddenly, you have an intimacy with Middle or Jacobean English. Milton’s formality loses its stiffness to reveal an intense passion. Pope’s stylistics melt into a thinly veiled bawdy farce…even for unsophisticated Midcentury Midwestern teenagers.

Hi Lori! Wow, interesting to hear that, and especially how memorising transforms the work. This knowledge enriches the ending of Fahrenheit 451 for me.

Superb explanation of the beat sheet methodology Roz, thank you!. I’ve been thinking about it since you first mentioned it, so this post was spot-on. It’s a much more evolved version of a technique I tried to put together for my own writing some time ago. Didn’t work out that well, if you’re wondering 🙂 This explanation pinpoints where the holes were in my attempt… I’m looking forward to trying out your method on the novel – it makes perfect sense. Thanks for sharing it.

Thanks, Jon! Have fun with it.